Michael Mann: Depicting larger-than-life figures on-screen

An analysis of Heat and Public Enemies and how they explore the cop-criminal relationship.

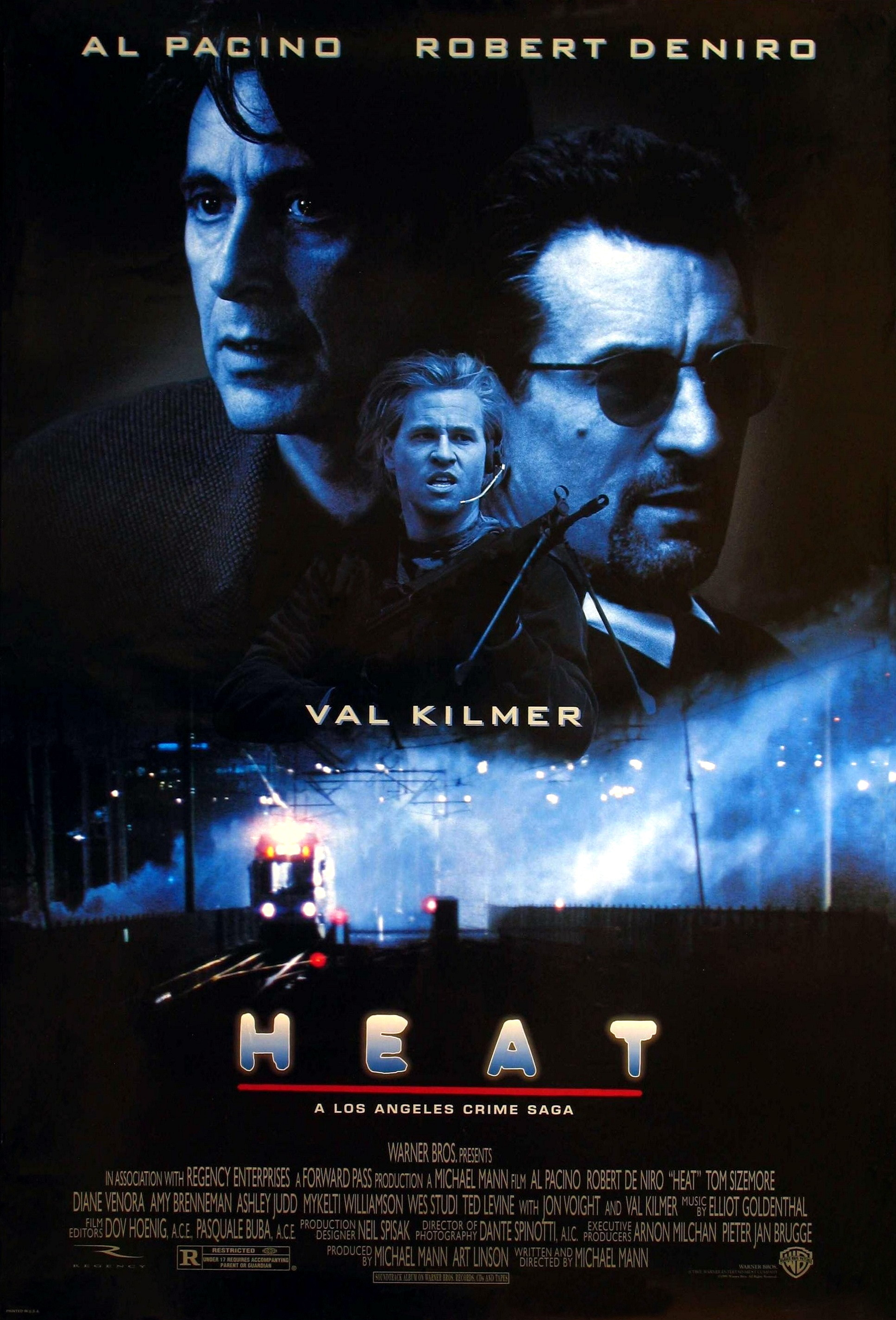

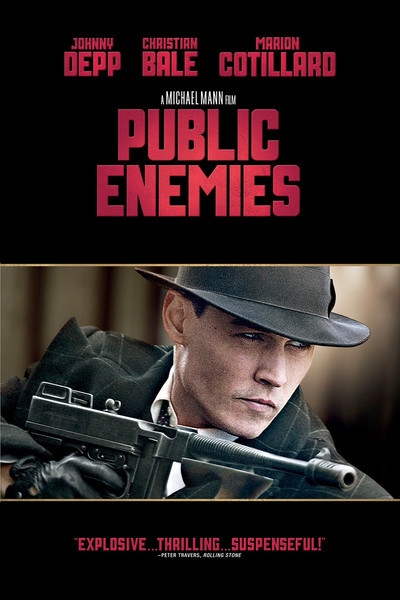

I’ve heard much about Heat (1995) in film circles. Directed by Michael Mann, it is lauded as one of those ‘must-see’ movies, leaving a clear legacy on the crime thriller genre as well as sadly real life robberies. Having recently had the pleasure of watching it for the first time, I wanted to continue watching Mann’s filmography and stumbled across Public Enemies (2009) on Netflix. As of writing this article these are the only two Mann films I have watched, but I thought there was already an abundance of content to discuss.

Note: This article contains full spoilers for both movies. However, hopefully this prompts you to at least give Heat a shot, or appreciate it a bit more on a re-watch. I don't recommend Public Enemies except for those who are fans of the actors, director or period crime-thriller genre.

Read below for my observations on how Mann uses the story, setting, camera and reality to capture larger-than-life figures on screen in Heat and Public Enemies, concluding with a discussion of what this means for cinema.

📝 Crime thriller plots

On the surface, the plots for both movies seem eerily similar despite their difference in time periods. Heat follows professional thief Neil McCauley and LAPD lieutenant Vincent Hanna. Both are cold-hearted experts at their job with not much room for anything else in their lives; McCauley must always be ready to escape his current life in thirty seconds, and Hanna’s marriage is failing due to his dedication to his work. Things change when Hanna gets closer to the thieving crew and McCauley finds enough love in a woman that convinces him to leave the game, therefore deciding to take one last job.

Public Enemies is set in the 1930s and follows notorious real-life bank robber John Dillinger and Melvin Purvis, the G-man (FBI agent) hunting him. Both are shown as more light-hearted characters who are still experts at their job, but with less detail around their non-work lives than that of Heat. Things change when Purvis gains more support to hunt down the bank robbers, and Dillinger finds enough love in a woman that convinces him to leave the game, therefore deciding to take one last job.

Seeing the similarities already? At first I found it frustratingly funny, but as the stories went on it became much more interesting to watch for the discrepancies and nuances between the two films.

👮 The cop-criminal ‘code’

The centre of Heat and a large focus of Public Enemies is the relationship between the man on the right side of the law and the man breaking it. In both films the criminal is actually the more sympathetic one. McCauley and Dillinger are painted as humanistic and romantic. Comparatively, Al Pacino has stated that Hanna’s character was meant to be strung up on cocaine, and Purvis finds himself resorting to unethical methods to obtain his information.

This brings up the point that on both sides there are certain lines you do not cross. Both films' respective main criminals show more respect towards women than most of their company, and they don’t work with law-breakers who endanger the lives of their crew or are mentally unhinged. McCauley and Dillinger treat their teams with respect, but hold the final say - in such a small group there is no need for bureaucracy. On the other hand, Hanna and Purvis find themselves restrained by the bounds of being a police officer at times. They must find information lawfully, engaging with other criminals (informants, brothel owners) and bending but always remaining within the rules established. They cannot even arrest the man they are hunting unless he is directly breaking the law at that time, or within their state’s jurisdiction.

Then there is always the issue of their boss and co-workers, who have separate agendas and levels of interest in the actual case that is the focus of these two officers’ lives. Whereas Purvis is more removed from the case than Hanna is, Mann introduces ex-military agents who assist Purvis on the case. Hanna is a manic detective trying to stay one step ahead of his intelligent criminal opponent; but Purvis embodies the idealistic officer of the 30s who turns a blind eye to the darker, yet necessary work done by the hardened men helping him.

Both movies have a criminal-cop confrontation only once. In Heat, this occurs around the midpoint and is oft hailed as one of the great conversations between two experienced actors. McCauley and Hanna speak in a cafe, seemingly open whilst holding the important cards close to their chests. The characters threaten each other yet contemplate the similar struggles between their lines of work. This is a clear highlight of the movie, and a scene with nail-biting tension yet so much great character work demonstrated through the dialogue.

Alternatively, Public Enemies shows how Dillinger whispers his final words into the ears of one of the officers hunting him whilst bleeding out on the pavement. Unlike Purvis, who led the hunt but ultimately remains abreast of his target, it is the steely-eyed Winstead who hears Dillinger’s final breath. What was most interesting to me was the fact that when Purvis asks, Winstead lies to his commanding officer and says he could not discern Dillinger’s last words. It is only in the film’s final scene when Winstead is alone with the woman for whom Dillinger was ready to leave it all behind that he reveals the truth. Dillinger died thinking of the woman he loved, and despite being his opposite, Winstead respects the man’s privacy. He delivers the message to the heartbroken Frechette, then leaves promptly, giving the impression that this is one of the many routine tasks involved in this line of work.

👴 Actor’s expressions

Heat's ending is similar to that of Public Enemies. McCauley ultimately cannot escape the long arm of the law, and after a tense shootout sits bleeding from Hanna's bullet. As he breathes his final breaths, there is a single line of dialogue and a look shared between the two characters. McCauley reaches out, and Hanna grips his hand like that of a brother. Despite being enemies, the viewer gets the sense that these two characters understand each other best out of the entire film’s cast. It is truly a haunting yet surprisingly beautiful ending to the film, the cat-and-mouse game concluding not in glory but resignation to their individual roles as the policeman and the criminal who gets caught.

What makes this final scene of Heat work so well is the unbelievable acting of the leads. Both renowned for their work in the crime thriller genre, it’s hard to believe that before Heat Al Pacino and De Niro had not yet shared the screen (they were both involved in The Godfather II but did not have any scenes together). What they bring to their roles are nuanced expressions, an understanding of backstory that doesn’t even need dialogue to express it. With a handful of lines in the early scenes and some rough physical alterations the viewer is able to instantly grasp who each of these men are and what their past is like.

Depp takes a different approach against Bale’s straight-man in Public Enemies. Despite being a criminal, Dillinger is actually a growing celebrity and thus has a few more smiles in public to cover the emptiness inside that his line of work has brought him. What I love about cinema is that a change in camerawork can dramatically change an already great performance. Mann loves wide shots, really increasing the size of an actor or pitting them against a practical (not green-screen) setting. When the camera gives us a close up of McCauley’s intense gaze, or a wide shot of a smiling Dillinger looking at his own wanted posters, these characters become larger-than-life figures. Yes, they’re human and relatable - Mann’s dialogue and each actor’s expression ensures that - but they are also overwhelming; we are captivated by their emotions as they are amplified on a large screen. I don’t think I would hold the same level of attention towards these actors if I was watching a faster-paced cut or smaller format such as a TV serial.

As a side note, Mann uses the telephoto lens with no refrain in Heat which I believe adds a lot of success to the film's framing. He experiments later with digital cameras in Public Enemies, but I found the heightened frame rate and sense of realism off-putting for the film's historical content.

🌆 The city as a backdrop

The cinematic format isn’t just great at capturing faces, but Mann brilliantly frames the actor’s figures against their respective cities. Personally, I first heard about Heat from Christopher Nolan, who cited it being an inspiration for him when crafting Gotham City and the Batman-Joker relationship in The Dark Knight. Admittedly, this is not explored as well in Public Enemies with Dillinger jumping from place to place. We do however see the growth in the FBI through the changing backgrounds during Purvis’s pursuit. I also feel that when filming Public Enemies, Mann was more concerned in capturing reality and recreating historical details such as the rusted bars and cement in a prison cell, or a bustling 1930s town. It’s really Heat that displays this notion of the location as a character as much as a beautiful backdrop.

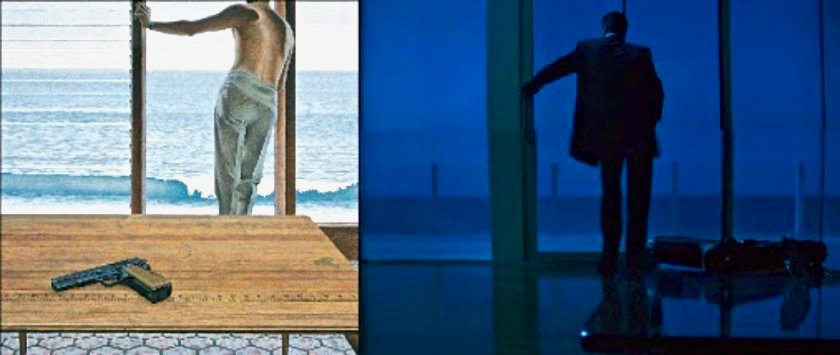

Mann shows us McCauley’s internal struggle for a non-criminal life by recreating Alex Colville’s 1967 painting “Pacific” on-screen. He emphasises the difficulty in Hanna’s hunt by putting an implausible yellow dust pile behind his partner, subtly signalling a dream-like quality in the plot, and the way McCauley slips through his fingers. Both characters are given space to breathe against this huge city, and the houses they reside in are modern architectural symbols of the lifestyles they lead - minimalist and empty for McCauley; cluttered chaos for Hanna.

I had the pleasure of recently visiting LA, and was left stunned at the evening city view from the Griffith Observatory. When watching Heat I made the mistake of believing Mann romanticised or edited the sprawling night view, adding a twinkling effect to the lights so that they look like stars. However this is a real effect - LA looks beautiful from a distance, lights blinking in and out while all you can hear is the wind covering the remote city sounds. These backdrops don’t just add to character, they are their own character playing off the moods of the cop and criminal in their chase. At times, it is just McCauley and Eady against a single-toned background - almost a homage to the soliloquies of plays of old, where characters would stand against blank backgrounds to speak their mind directly to the audience and each other.

There are many more locations of note, whether the isolated hospital or train station, the crowded backspaces of a hotel or the flaring lights and sounds of the LAX Airport. It is only fitting then that at the end of Heat McCauley and Hanna are just outside of the city, captured in darkness. They are the only characters in this denouement, as their respective characters and relationship stands alone against the world.

💥 Visceral noise

Both Heat and Public Enemies ground you in the action immediately by assaulting your senses during these sequences. Mann opted not to use soundstages for any of the action sequences during Heat, and carefully placed microphones around the set to capture the gunfire noises. This creates one of the film’s best action sequences, a long-winded but realistic gunfight on a wide road. Each shot and its echo is depicted with unnerving realism - it can be really off-putting to the viewer - but is actually much more plausible than the unrealistic gun action of 80s Hollywood films.

I foolishly thought this level of gun noise would be a one-off in Heat. Yet Public Enemies has its fair share of shootouts, including a particularly notable scene with a wooded building in a forest around the film’s midpoints. Both Heat’s bright road-based and Public Enemies’ dark lodge shootout reflect the periods of their characters, and explode with satisfying verisimilitude. Pulpy wood shatters into splinters; cop cars are dented. And in both scenes McCauley and Dillinger operate their criminal crews like pros, providing cover fire and moving people off in different directions at appropriate intervals.

It would be remiss of me not to mention the soundtracks. Public Enemies initially uses a heroic country-based theme in Ten Million Slaves. Played on banjo and electric guitar simultaneously for Dillinger, the track reinforces his popular status during the 30s and historical significance as one of the first modern celebrities. However towards the film’s third act a more somber theme emerges on strings aptly titled JD Dies, not just foreshadowing but impacting Dillingers eventual death and the pain this brings Frechette.

Elliot Goldenthal’s score for Heat is an eclectic mix of stylised rock, jazz and ethereal tracks that create a distinct soundscape for the film. Yes, Heat is set in the 1990s but it also is timeless in a way, capturing various styles and blending them together in a unique audio setting for the film’s hunt. When some aspects of the movie threaten to break down its sense of realism (for example the romance) both the camera with its wide backdrops, and the soundtrack with its slow-paced or driving rhythms, enter to save the story.

📽️ What this means for cinema

With the recent global pandemic keeping people at home and away from large gatherings, there has been a slow and steady but reluctant return to public theatres and cinema settings. Understandably everyone wants to keep their distance and sitting inside a crowded room packed with people eating, drinking and breathing for over two hours is not ideal when your goal is to remain pathologically safe. What this has done however is allowed films designed for streaming platforms to rise in popularity. These movies are faster-paced, choppier, evidently more digital-based in photography and background. It’s hard to justify cutting two to three hours out of your day for a movie when you could just watch a high-quality TV episode that lasts for one hour.

However some content is just made for movie theatres. Heat has stood the test of time as a cinematic classic, and although Public Enemies is not as acclaimed, they are both evidence that Mann continues to push his filmic storytelling forward within the crime thriller genre. Despite this, he recently released a series on HBO Max called Tokyo Vice, another sign that streaming TV quality will continue to rise for years to come. But for most of us, watching from home is not the same as letting yourself be completely drawn into a story in a dark room for two hours with no distractions from the outside world. Not all of us have gigantic projectors or surround sound quality, yet we do have neighbours who may put in a noise complaint at the startling sound of gunfire.

Watching Heat made me realise that some wide shots are best seen in theatres. Watching Public Enemies reinforced an understanding that quality filmmakers exploring their own genre or subject matter niche deserve our monetary compensation. And seeing everyone slowly return to movie-sized screens amongst the rise of streaming platforms gives me hope for future slow, loud and cinematic experiences.

🎞️ Thank you for reading the article!

🎥 As always, you can find more film reviews on my Letterboxd account here 😄